Antonio Canova’s opera

Antonio Canova (Possagno, November 1, 1757 – Venice, October 13, 1822) was one of the greatest sculptors not only of the neoclassical period but also one of the greatest artists ever, as well as Raphael, Michelangelo, and Caravaggio.

Through his technical and intellectual experiences, Canova became the emblem of neoclassical art, of the taste for perfect symmetries, soft and smooth surfaces, solemn and controlled poses, and impassive expressions, but without passively imitating the ancient, nor, at the same time, proving to be totally closed to Baroque art, as revealed by his admiration for the virtuosity of Bernini and the Venetian Antonio Corradini, a specialist in the rendering of female figures covered by transparent veils.

Canovian works achieve perfection: the balance between ideal and natural beauty is the result of the study of ancient and modern artists, nature is investigated and he kept in mind the lesson of painting, both in compositional aspects and pictorial effects that he was the only one able to mix it with his sculptures. There are many themes addressed by Canova in his works: from religious subjects to funerary monuments, often dedicated to the nobles of the time, to portraits of his patrons who, through his chisel, aspired to become immortal by taking on the likeness of mythological characters.

Antonio Canova, Pauline Borghese Bonaparte as Venus Victrix, 1804, plaster, Possagno, Museo Gypsotheca Antonio Canova

How did Antonio Canova work?

Francesco Hayez reported that: “Canova made his models in clay; cast in plaster, different good young men helped him with rough-hewing the marble. Two of them, then become famous sculptors, brought it to the degree of fineness, which would be said to be finished; nevertheless they had to leave a small coarseness of marble still, which was by Canova worked according to what this illustrious artist believed he had to do.” One of these two sculptors was Johann Peter Kauffmann from Germany, grandson of the famous painter Angelika. Complex method to hear it described directly by a witness, but unique in Canova’s practice.

In Rome the Artist had frequented the most active sculpture studios, where casts, copies and restorations were made. Indeed, there, workshops for the restoration of archaeological finds from excavations, demolitions and reconstructions of buildings and sculpture studios, where ancient sculptures were copied, were very active. Among these, those of Bartolomeo Cavaceppi and Carlo Albacini were frequented by the Venetian sculptor who discovered there the “cavar punti” method: making a copy using small bronze pegs applied to a model that served to transfer the dimensions into the marble block.

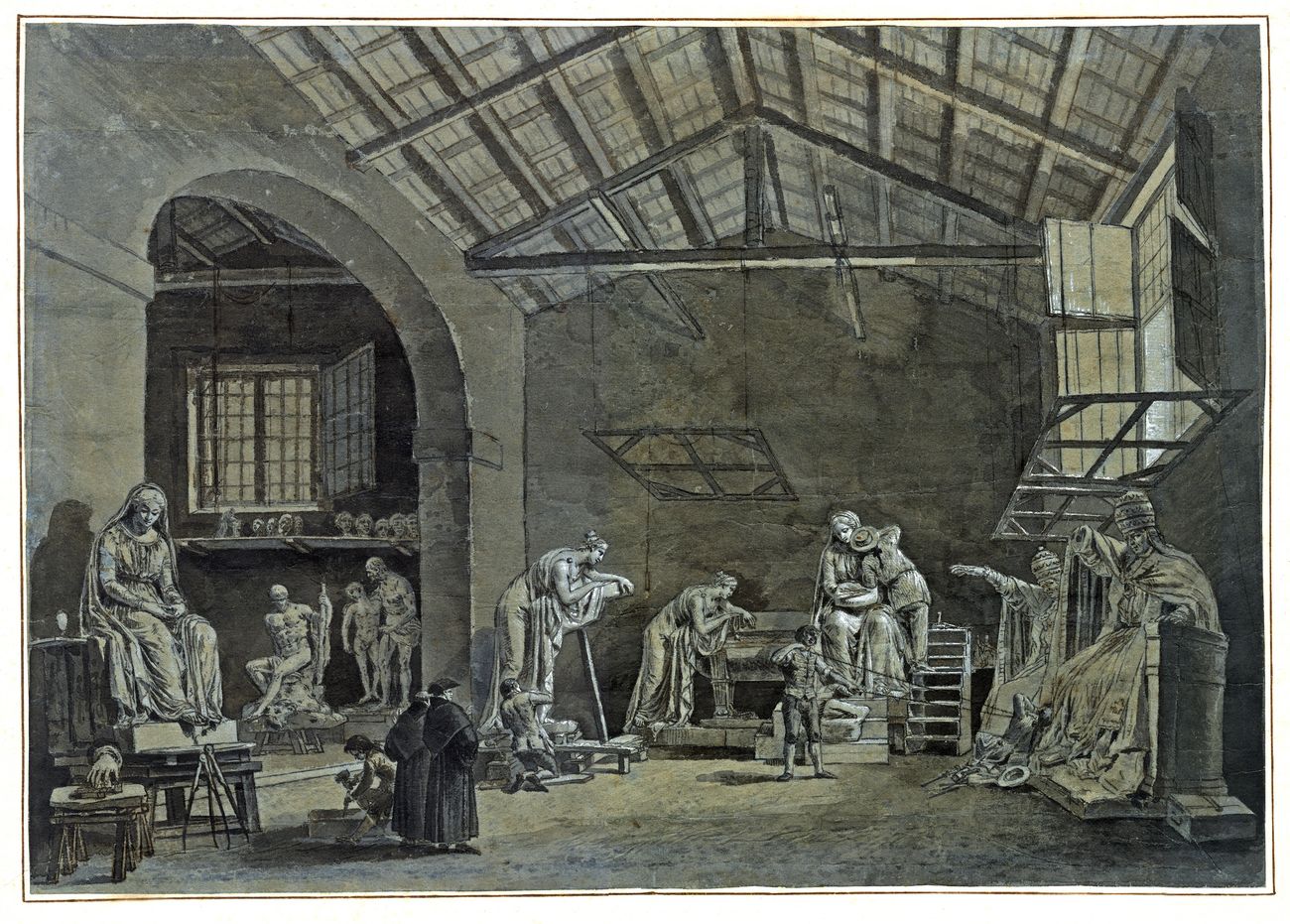

Francesco Chiarottini, Canova’s studio, 1786, gray and sepia watercolor ink drawing, heightened with white, Udine, Musei Civici

Francesco Chiarottini, a Friulian artist, represented, in one of his drawings, Antonio Canova’s workshop between March and June 1786. In that year the sculptor was working at the Funeral Monument to Clement XIV: while realizing this work, he adopted for the first time that specific procedure that would characterize his sculptures.

On the right of the drawing, you can see the plaster model of the figure of Pope Clement XIV and the corresponding marble sculpture. The latter lacks the right hand, which can be seen on a stool on the opposite site of the room. The two sculptures, the plaster model and the marble, are situated under a wooden structure. In the foreground, two of his assistants are working with a rope drill. In the background, on the shelf on the left where there are some heads/busts, you can also notice the small sculpture model that is now preserved at the Gypsotheca of Possagno. The two statues of Humility and Temperance are situated in front of the central wall. Two other assistants are doing the finishing touches. The plaster model of Humility is situated on the left and two pantographs are placed on the base.

In the center two visitors are observing the intense work and two apprentices are roughing marbles. In the room on the left, you can also see the two sculptures of Daedalus and Icarus, given to Venetian ambassador Girolamo Zulian, and Theseus and the Minotaur, sold to the Austrian patron Joseph von Fries.

From sketch to marble

Antonio Canova was highly skilled at carving and finishing marble and, although he ran a busy workshop of assistants, he insisted on finishing every one of his works himself. His balanced, graceful forms, treatment of nude or lightly draped bodies, and smooth, finely polished surfaces, produced sculptures that had lifelike presences. The execution of these sculptures required various stages of work:

Sketch

This first phase, the one of ‘invention’ and ‘arrangement’, consisted in the creation and study of the subject via preparatory sketches. Canova’s sketches were focused on finding the best solutions to light up the figures, by studying their poses and recalling the models of antiquity.

Bozzetti

Made in terracotta or wax, the “bozzetti” were used to evaluate the three-dimensional rendering of the sketches. It is common to see in the bozzetti in terracotta some Canova’s fingerprints.

Terracotta sketches by Antonio Canova

Terracotta sketches by Antonio Canova

Small plaster model

Canova sometimes produced also small plaster models. Some of these models are preserved in the Gypsotheca: George Washington, Theseus and the Minotaur, Theseus and the Centaur, Funeral Monument to Horatio Nelson, Funeral Monument to Clement XII, A Crying Italy.

Full-scale clay model

Canova realized the models in clay on the same scale as the final artworks in marble. These models, which were then destroyed, were fundamental for the later creation of the full-scale model in plaster.

Models and little models inside the first room of the Gypsotheca |

ph. Otium/Favotto

Forma

To create the “forma”, plaster was poured on/over the full-scale clay model. The clay model was then destroyed, and the solidified “forma” filled with liquid plaster and a metallic weight-bearing structure.

Full-scale plaster model

It was created by the solidification of the plaster inside the “forma”. When the “forma” was opened, the model was smoothed and some small bronze nails, called repères, were inserted all along the surface. These metallic spots were marked as reference points to transfer the plaster image to marble.

Antonio Canova’s technique, tools for measuring repères

Antonio Canova’s technique, the cast

Repère

Chiodini di bronzo (generalmente realizzati con una lega di bronzo ottenuta dalla fusione di zinco, rame e stagno) collocati sul mo dello di gesso. Quelli più sporgenti venivano chiamati “punti chiave o capi punto”. Con compassi si procedeva a calcolare le distanze degli altri punti.

Sculpture in marble

Canova had an elaborate system of comparative pointing so that his assistants were able to reproduce the plaster form in the selected block of marble. Once the plaster model was placed next to the marble, the same points were repeated on the block of stone via the use of compasses, pantographs, and plumb-lines on a scale of 1:1. This method allowed a quite faithful transposition and reproduction of the original design in plaster. His assistants would then leave a thin veil over the entire statue so Canova’s could focus on the surface of the sculpture.

The “ultima mano”

The conclusive phase was reserved for Canova: he used all of his technical expertise to clean and polish the surfaces and forms, giving the statue its definitive aspect. Moreover, the sculptor usually applied a mixture of wax and other substances to the marble to evoke the flesh’s softness and eliminated the stone’s shiny quality.

Canova

2019, Magnitudo film

In this piece dott. Mario Guderzo tells

Antonio Canova’s technique